It happened with social justice, and then again with equity. Must you whiten anti-racism too?

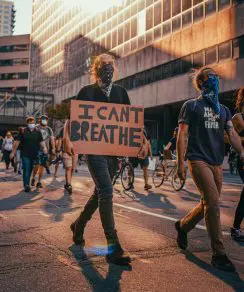

In the last month since the unfortunate violent, public modern-day lynching of a Black man, George Floyd, and the global wave of Black Lives Matters protests, books on anti-racism have dominated the top ten of bestseller lists. And now the media has become quite cavalier with the word anti-racist, throwing around the term as a descriptor for anything and everything from anti-racist reading lists and book festivals, anti-racist organizations to donate to, how to be an anti-racist ally, how to create an anti-racist workplace, and even how to raise an anti-racist child or baby. A lens designed for systemically taking action against racism that I value is now becoming whitewashed and used for capitalistic gains.

As a scholar on anti-racism who believes in the power of anti-racist practices if approached systemically, I have recently struggled with how anti-racism has now all the sudden become a trend. I have a co-authored book with Dr. Sarah Diem on Anti-racist Educational Leadership and Policy that will be released next month, a book project we hope will assist educational leaders in working collaboratively with their school communities to think critically about the racial implications of the policies they design and implement. We were initially hesitant to tweet and share out about our book, work that we are indeed proud of, given the current circumstances where anti-racism is now all the sudden trendsetting. I have my own set of reservations about the fact that white folx may flock to my scholarship on anti-racism just to deal with their own guilt about, and newfound realization of, how they may have perpetuated racism and even anti-Black racism in education.

As a Black female professor in the field of educational leadership and policy who teaches at a predominately white institution, my class enrollment is usually dominated by white educators who are preparing to become principals or superintendents—something else I and definitely the field as a whole still needs to work on. Research in the K-12 educational leadership field for a long time focused specifically on white, male-centric managerial frameworks that took more of a business approach to practicing educational leadership. So, it was seen as revolutionary when, in the early 2000s, the field began to center on social justice. Social justice at its core should be a systemic effort to upend interlocking forms of oppression in education. But the concept soon became a globally trendy mantra with not much traction for real change, especially with the problematic proclamation of being a “social justice warrior” or famous quotes from anti-Apartheid and human rights activist Desmond Tutu, which were turned into T-shirt slogans.

Then in the mid 2000s the education profession decided to try out the concept equity, and that image of the three kids sitting on the boxes at different levels staring over the fence at a baseball game became the go-to for our collective sensemaking of the term. I have even used this image in professional development talks I’ve given in the past, but still equity appeals to whiteness and that fence in this noted image also represents whiteness. This particular image equates equity to a mere survival tactic for those minoritized by education. With equity we are simply giving each student what he or she needs to succeed in surviving the structures of whiteness and white supremacy in education. Thus, equity becomes a deficit concept that focuses on fixing youth and adult learners while allowing white norms in education to remain intact. Case in point, national educational reforms like the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) for K-12 and the Perkins V Act for career and technical education are both now requiring states to include equity in their plans for rolling out the reforms. However, many states are simply wordsmithing by adding language to their plans that appeases federal mandates, with little actionable changes that would level the playing field for minoritized students.

With equity we are simply giving each student what he or she needs to succeed in surviving the structures of whiteness and white supremacy in education.

So, what exactly then is anti-racism? In an article I co-authored with Drs. Devean Owens and Eboni Zamani-Gallaher on anti-racist change, we argue that the concept of anti-racism should extend beyond “just talk” about how educational institutions are going to change. This anti-racist talk with no substance or follow-through usually comes in the form of emailed statements condemning racism issued by top-level leaders or one-off diversity workshops that never generate any critical discussion about what then leads to actual changes that redress racism in policies, procedures, and practices both at the institutional and classroom level. In our article, we argue that anti-racism is actually a systemic project, and those working to achieve racial justice in their institutions or organizations should not just focus on changing individuals’ racial biases and attitudes but should also attempt to address changing the system as a whole. One mistake we often see is that educators spend so much time on trying to change the hearts and minds of their colleagues when it comes to redressing racism, and they never even get to systemic-level work. So, in this article, we developed a framework that practitioners can use for actionable and systemic anti-racist change.

So, for white people who are newly immersing in anti-racist literature, you should not call yourself anti-racist at this early stage of learning. Anti-racism is a journey. Anti-racism is something you are constantly working on to do better and improve upon, not just in the short-term but consistently over the long run. Anti-racism is daily, ongoing work and actions toward righting racial wrongs. Anti-racism is more than just reading about the effects of racism but is also the willingness to take what you have learned and then doing the hard work of questioning and putting an end to norms, structures, policies, and practices that are racially harmful, and then starting anew by rebuilding educational systems and institutions that prioritize racial justice.

Also, anti-racism is doing the revolutionary work needed to achieve racial justice even if it means you will lose many of your privileges as a white person as a result. So, the truth of the matter is that at this stage of your journey, it is more accurate to refer to yourself as newly conscious of and aware of racism, and hopefully this is inclusive awareness of anti-Black racism. Don’t give yourself a pat on the back just yet, as you still have a lot of learning and real work to do toward anti-racist change.

When immersing yourself in anti-racism readings, tools, scholarship, and engaging in anti-racist practices, here are some recommendations:

- As a starting point, examine anti-Blackness. As the Black Lives Matter movement is teaching us, much of white privilege and racism in educational institutions and organizations is in direct correlation with anti-Blackness and the devaluation of Black people. For white privilege and whiteness to maintain and work, it relies on the denigration of Black, Indigenous and racially minoritized groups. Begin by learning about the history of anti-Blackness, how the fabric of our nation was established on anti-Blackness. Next, deconstruct how current policies, structures, and practices in the educational institutions where we work and learn are designed to fuel anti-Blackness. Acknowledging how anti-Black racism operates at your institution is the first step to addressing it head on.

- Select readings and resources on anti-racism with some sense of criticality. Just because a book, an article, an op-ed, or even an infographic uses the word anti-racism doesn’t mean it is of quality. Practice a level of criticality and discernment when searching for readings on anti-racism to inform your practice. Look for readings and resources on anti-racism that provide a holistic and systemic approach to redressing racism that goes beyond examining anti-racism in a theoretical sense but also provides practical examples as well.

- Anti-racism should be systemic change, not piecemeal and sporadic. When strategizing and organizing to achieve racial justice, the process should not be piecemeal by tackling a little bit here and a little bit there. Racism is systemic; if you address one component of it at a time you will never get anywhere, because while you are working on that one small part of the problem, the rest of the problem will continue, fester, and grow. Plus, whiteness and white supremacy’s growth and success are inversely tied to the slowness in which institutions address racism and work toward racial justice. Therefore, do anti-racist work systemically by addressing racial biases, the relationships between individuals and groups that perpetuate racism, and racist policies, structures, and practices simultaneously. And of course, ensure that this work is ongoing.

- Don’t read anti-racist resources because you want something to quell your white guilt. Finally, begin this journey of adopting an anti-racist mindset and practice not because you need something to absolve you of your guilt about your role in perpetuating racism, but because you truly are ready to do the hard work necessary to achieve systemic racial justice in education. Many white leaders and predominately white institutions are releasing anti-racism statements as a means of weathering this current moment. Truth be told, history has shown these displays to be empty declarations. Right" now, we need leaders to make the enormous consequential changes required in addressing American racism.