Over two million women and men are incarcerated in American jails. There is critical need for us to move from negligence to intentionality in fostering a pipeline to postsecondary and away from prisons.

According to Kilgore (2015), one-quarter of the prison population worldwide resides in the United States penal system yet Americans only comprise five percent of the total world population. The majority of those serving time are overwhelmingly from underserved communities with large numbers of low-income, people of color disproportionately behind bars. African Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population, but 2 of every 5 inmates are African American. Latinos account for 14% of the population, but 1 of every 5 inmates are Latino/a (Mauer & King, 2007; U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).

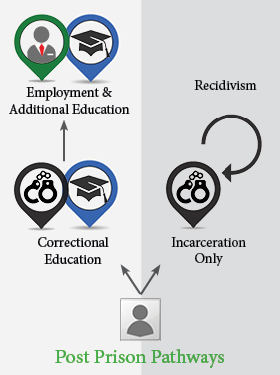

The cost of maintaining the prison system to taxpayers is substantial. Each year over $80 billion dollars is spent on incarceration in the U.S. (American Civil Liberties Union, 2016). Seventy billion of taxpayer dollars fund state and federal prisons and states expend between $52-62 billion dollars on prison maintenance (Zoukis, 2014). Roughly 5% or fewer inmates enroll in prison postsecondary education programs; largely vocational certificate programs (Erisman & Contardo, 2005). Hence, more annual spending goes toward operating, maintaining, and building prison facilities than spending on basic/life skills education or academic courses beyond the high school diploma. Research has noted that postsecondary prison education positively affects the odds of employment following incarceration (Duwe & Clark, 2014; Langemann, 2015; Lockwood, Nally, Ho & Knutson, 2012). However, despite evidence that correctional educational reduces crime rates and recidivism, limited investment in correctional education and limited access to correctional education continue to be the norm (Bazos & Hausman, 2004; Davis, et al., 2013, 2014).

With growing inequities evident in the correctional system, it is imperative that college access reach all populations, including incarcerated individuals. Recent activities that focus on building this access and uplifting inmates are promising. In observance of National Reentry Week, April 24-30, 2016, the Bureau of Prisons as authorized by the Department of Justice hosted mentoring exchanges, family days, job fairs, educational forums, and a host of other events. As programming designed to help prepare inmates for release wrapped during National Reentry Week, the week of May 2nd was eventful with President Obama hosing a prison education reform meeting at the White House. In attendance for the prison reform conversation was University of Illinois Professor Dr. Rebecca Ginsburg who serves as Director of the Education Justice Project (EJP), which is a prison education program with collaboration between UIUC, Danville Area Community College, and Danville Correctional Center. Announced May 5, 2016 in his blog A Nation of Second Chances, the President shared his granting of 58 new clemencies and highlighted those who previously granted clemency that were able to self-actualize and maximize their commuted sentences.

On May 9, 2016, U.S. Department of Education Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE) announced the release of Beyond the Box: Increasing Access to Higher Education for Justice-Involved Individuals This publication is a guide for colleges and universities to reassess the necessity of prior involvement with the justice system in admissions decisions, encourage access and support services across student populations, and encourage the abandonment of unwarranted hurdles to prospective students irrespective of association with the department of corrections.

If the U.S. is to have a productive and educated populace that is globally competitive in today’s diverse knowledge economy, then we must acknowledge the grave implications of a failure to extend college to the masses. Neglecting to broaden participation to prisoners in postsecondary programming can only serve to reproduce the cumulative disadvantaging of this population and dim the lights on how bright we could all shine because of not enacting practices that produce rich outcomes for inmates. Opportunities for access to postsecondary education and educational equity in general for incarcerated individuals are lacking. There is critical need for us to move from negligence to intentionality in fostering a pipeline to postsecondary and away from prisons. Community colleges are the sector of higher education that is uniquely situated at the intersection of postsecondary access and opportunity, and as such, uniquely situated to facilitate correctional education. Community colleges are also key in efforts to building educational equity necessary as part of the work of redirecting the pipeline to prison and building in its place a pipeline through education to opportunity.

To read more on prison education and the role of community colleges in fostering access, see the Update on Research and Leadership FEATURE brief, Altering the Pipeline to Prison and Pathways to Postsecondary Education.

References

- American Civil Liberties Union (2016). Mass incarceration.

- Bazos, A. & Hausman, J. (2004, March). Correctional education as a crime control program. UCLA School of Public Policy and Social Research.

- Davis, L. M., Steele, J. L., Bozick, R., Williams, M., Turner, S., Miles, J. N. V., Saunders, J. & Steinberg, P. S. (2014). How effective is correctional education and where do we go from here? The results of a comprehensive evaluation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Duwe, G., & Clark, V. (2014). The effects of prison-based educational programming on recidivism and employment. The Prison Journal, 94(4), 454-478.

- Erisman, W., & Contardo, J. (2005). Learning to reduce recidivism: A 50-state analysis of postsecondary correctional education policy.

- Kilgore, J. (2015). Understanding mass incarceration: A people's guide to the key civil rights struggle of our time. NY: The New Press.

- Langemann, E. C. (2015, November). College in prison: A cause in need of advocacy and research. Educational Researcher, 44(8), 415-420.

- Lockwood, S., Nally, J. M., Ho, T., & Knutson, K. (2012). The effect of correctional education on postrelease employment and recidivism: A 5-year follow-up study in the state of Indiana. Crime & delinquency, 58(3), 380-396.

- Mauer, M., & King, R. S. (2007, July). Uneven justice: State rates of incarceration by race and ethnicity. Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project.

- Mercer, K. R. (2009). The importance of funding postsecondary correctional educational programs. Community College Review, 37(2), 153-164.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2015, September). U.S. Census Bureau: State and county quick facts. Washington, DC: Author.

- Zoukis, C. (2014). College for convicts: the case for higher education in American prisons. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.